People fishing along the banks of the White River as it winds through Indianapolis sometimes pass by ominous signs warning about eating the fish they catch.

One of the risks they have faced is mercury poisoning.

Mercury is a neurotoxic metal that can cause irreparable harm to human health – especially the brain development of young children. It is tied to lower IQ and results in decreased earning potential, as well as higher health costs. Lost productivity from mercury alone was calculated in 2005 to reach almost $9 billion per year.

One way mercury gets into river fish is with the gases that rise up the smokestacks of coal-burning power plants.

The Environmental Protection Agency has had a rule since 2012 limiting mercury emissions from coal-fired power plants. But the Trump administration stopped enforcing it, arguing that the costs to industry outweighed the health benefit.

Now, the Biden administration is moving to reassert it.

I study mercury and its sources as a biogeochemist at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis. Before the EPA’s original mercury rule went into effect, my students and I launched a project to track how Indianapolis-area power plants were increasing mercury in the rivers and soil.

Mercury bioaccumulates in the food chain

The risks from eating a fish from a river downwind from a coal-burning power plant depends on both the type of fish caught and the age and condition of the person consuming it.

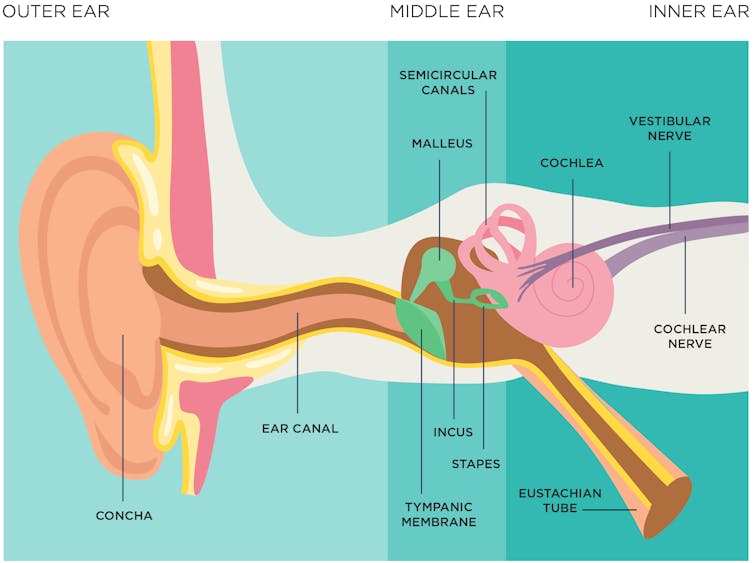

Mercury is a bioaccumulative toxin, meaning that it increasingly concentrates in the flesh of organisms as it makes its way up the food chain.

The mercury emitted from coal-burning power plants falls onto soils and washes into waterways. There, the moderately benign mercury is transformed by bacteria into a toxic organic form called methylmercury.

Each bacterium might contain only one unit of toxic methylmercury, but a worm chewing through sediment and eating 1,000 of those bacteria now contains 1,000 doses of mercury. The catfish that eats the worm then get more doses, and so on up the food chain to humans.

In this way, top-level predator fishes, such as smallmouth bass, walleye, largemouth bass, lake trout and Northern pike, typically contain the highest amounts of mercury in aquatic ecosystems. On average, one of these fish contains enough to make eating only one serving of them per month dangerous for the developing fetuses of pregnant women and for children.

How coal plant mercury rains down

In our study, we wanted to answer a simple question: Did the local coal-burning power plants, known to be major emitters of toxic mercury, have an impact on the local environment?

The obvious answer seems to be yes, they do. But in fact, quite a bit of research – and coal industry advertising – noted that mercury is a “global pollutant” and could not necessarily be traced to a local source. A recurring argument is that mercury deposited on the landscape came from coal-burning power plants in China, so why regulate local emissions if others were still burning coal?

That justification was based on the unique chemistry of this element. It is the only metal that is liquid at room temperature, and when heated just to a moderate level, will evaporate into mercury vapor. Thus, when coal is burned in a power plant, the mercury that is present in it is released through the smokestacks as a gas and dilutes as it travels. Low levels of mercury also occur naturally.

Although this argument was technically true, we found it obscured the bigger picture.

People fishing along the banks of the White River as it winds through Indianapolis sometimes pass by ominous signs warning about eating the fish they catch.

One of the risks they have faced is mercury poisoning.

Mercury is a neurotoxic metal that can cause irreparable harm to human health – especially the brain development of young children. It is tied to lower IQ and results in decreased earning potential, as well as higher health costs. Lost productivity from mercury alone was calculated in 2005 to reach almost $9 billion per year.

One way mercury gets into river fish is with the gases that rise up the smokestacks of coal-burning power plants.

The Environmental Protection Agency has had a rule since 2012 limiting mercury emissions from coal-fired power plants. But the Trump administration stopped enforcing it, arguing that the costs to industry outweighed the health benefit.

Now, the Biden administration is moving to reassert it.

I study mercury and its sources as a biogeochemist at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis. Before the EPA’s original mercury rule went into effect, my students and I launched a project to track how Indianapolis-area power plants were increasing mercury in the rivers and soil.

Mercury bioaccumulates in the food chain

The risks from eating a fish from a river downwind from a coal-burning power plant depends on both the type of fish caught and the age and condition of the person consuming it.

Mercury is a bioaccumulative toxin, meaning that it increasingly concentrates in the flesh of organisms as it makes its way up the food chain.

The mercury emitted from coal-burning power plants falls onto soils and washes into waterways. There, the moderately benign mercury is transformed by bacteria into a toxic organic form called methylmercury.

Each bacterium might contain only one unit of toxic methylmercury, but a worm chewing through sediment and eating 1,000 of those bacteria now contains 1,000 doses of mercury. The catfish that eats the worm then get more doses, and so on up the food chain to humans.

In this way, top-level predator fishes, such as smallmouth bass, walleye, largemouth bass, lake trout and Northern pike, typically contain the highest amounts of mercury in aquatic ecosystems. On average, one of these fish contains enough to make eating only one serving of them per month dangerous for the developing fetuses of pregnant women and for children.

How coal plant mercury rains down

In our study, we wanted to answer a simple question: Did the local coal-burning power plants, known to be major emitters of toxic mercury, have an impact on the local environment?

The obvious answer seems to be yes, they do. But in fact, quite a bit of research – and coal industry advertising – noted that mercury is a “global pollutant” and could not necessarily be traced to a local source. A recurring argument is that mercury deposited on the landscape came from coal-burning power plants in China, so why regulate local emissions if others were still burning coal?

That justification was based on the unique chemistry of this element. It is the only metal that is liquid at room temperature, and when heated just to a moderate level, will evaporate into mercury vapor. Thus, when coal is burned in a power plant, the mercury that is present in it is released through the smokestacks as a gas and dilutes as it travels. Low levels of mercury also occur naturally.

Although this argument was technically true, we found it obscured the bigger picture.

We found the overwhelming source of mercury was within sight of the White River fishermen – a large coal-burning power plant on the edge of the city.

This power plant emitted vaporous mercury at the time, though it has since switched to natural gas. We found that much of the plant’s mercury rapidly reacted with other atmospheric constituents and water vapor to “wash out” over the city. It was raining down mercury on the landscape.

Traveling by air and water, miles from the source

Mercury emitted from the smokestacks of coal-fired power plants can fall from the atmosphere with rain, mist or chemical reactions. Several studies have shown elevated levels of mercury in soils and plants near power plants, with much of the mercury falling within about 9 miles (15 kilometers) of the smokestack.

When we surveyed hundreds of surface soils ranging from about 1 to 31 miles (2 to 50 km) from the coal-fired power plant, then the single largest emitter of mercury in central Indiana, we were shocked. We found a clear “plume” of elevated mercury in Indianapolis, with much higher values near the power plant tailing off to almost background values 31 miles downwind.

The White River flows from the northeast to the southwest through Indianapolis, opposite the wind patterns. When we sampled sediments from most of its course through central Indiana, we found that mercury levels started low well upstream of Indianapolis, but increased substantially as the river flowed through downtown, apparently accumulating deposited mercury along its flow path.

[Understand developments in science, health and technology, each week. Subscribe to The Conversation’s science newsletter.]

We also found high levels well downstream of the city. Thus a fisherman out in the countryside, far away from the city, was still at significant risk of catching, and eating, high-mercury fish.

The region’s fish advisories still recommend sharply limiting the amount of fish eaten from the White River. In Indianapolis, for example, pregnant women are advised to avoid eating some fish from the river altogether.

Reviving the MATS rule

The EPA announced the Mercury and Air Toxic Standards rule in 2011 to deal with the exact health risk Indianapolis was facing.

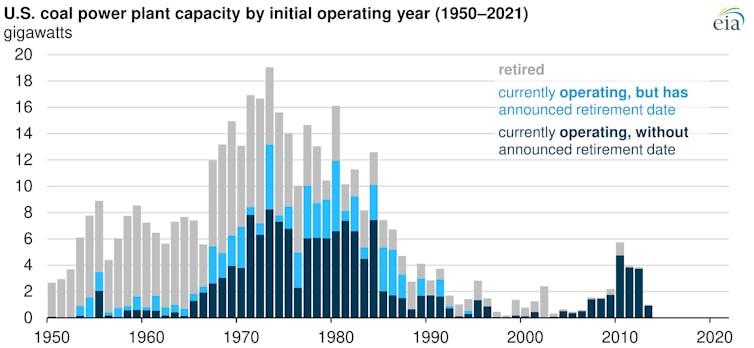

The rule stipulated that mercury sources had to be sharply reduced. For coal-fired power plants, this meant either installing costly mercury-capturing filters in the smokestacks or converting to another energy source. Many converted to natural gas, which reduces the mercury risk but still contributes to health problems and global warming.

The MATS rule helped tilt the national energy playing field away from coal, until the Trump Administration attempted to weaken the rule in 2020 to try to bolster the declining U.S. coal industry. The administration rescinded a “supplemental finding” that determined it is “appropriate and necessary” to regulate mercury from power plants.

On Jan. 31, 2022, the Biden Administration moved to reaffirm that supplemental finding and effectively restore the standards.