On Sept. 28, 2022, the U.S. House select committee investigating the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection will hold another public hearing – likely the last before it releases its official report.

Through earlier hearings this past summer, the committee has shown how former President Donald Trump and close associates spread the “big lie” of a stolen election. The hearings have also shown how Trump stoked the rage of protesters who marched to the U.S. Capitol and then refused to act when they breached the building.

The hearings have aired in prime time and dominated news cycles. Still, polling conducted in August by Monmouth University found that around 3 in 10 Americans still believe that Trump “did nothing wrong regarding January 6.”

As a sociologist who studies denial, I analyze how people ignore clear truths and use rhetoric to convince others to deny them, too. Politicians and their media allies have long used this rhetoric to manage scandals. Trump and his supporters’ responses to the Jan. 6 investigation are no exception.

Stages of denial

Commonly, people think of denial as a state of being: Someone is “in denial” when they reject obvious truths. However, denial also consists of linguistic strategies that people use to downplay their misconduct and avoid responsibility for it.

These strategies are remarkably adaptable. They’ve been used by both political parties to manage wildly different scandals. Even so, the strategies tend to be used in fairly predictable ways. Because of this, we can often see scandals unfold through clear stages of denial.

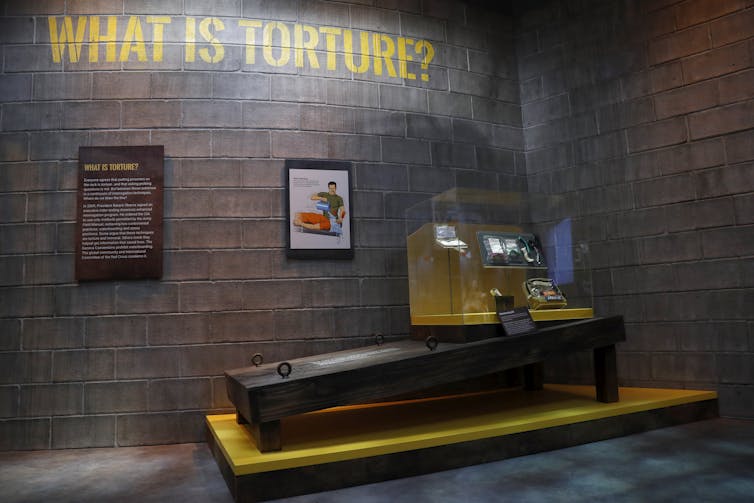

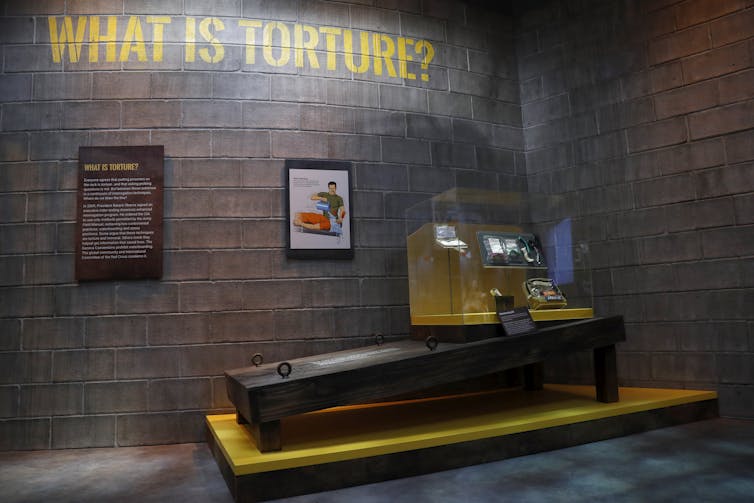

In my previous research on denial and U.S. torture, I analyzed how the George W. Bush administration and supporters in Congress adjusted the forms of denial they used as new allegations and evidence of abuses in the global “war on terror” became public.

For instance, after photographs of torture at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq were released in the spring of 2004, Abu Ghraib was described as a deplorable but isolated incident. At the time, there wasn’t serious public evidence of detainee abuse at other U.S. facilities.

Later revelations about the use of torture at Guantánamo Bay and secret CIA black sites changed things. The Bush administration could no longer claim that torture was an isolated incident. Officials also faced allegations that they had directly and knowingly authorized torture.

Facing these allegations, Bush and his supporters began justifying and downplaying torture. To many Americans, torture, once deplorable, was rebranded as an acceptable national security tool: “enhanced interrogation.”

As the debate about torture shows, political responses to scandal often begin with outright denials. But rarely do they end there. When politicians face credible evidence of political misconduct, they often try other forms of denial. Instead of saying allegations are untrue, they may downplay the seriousness of allegations, justify their behavior or try to distract from it.

It’s not just Republican administrations that use denial in this way. When the Obama administration could no longer outright deny civilian casualties caused by drone strikes, it downplayed them. In a 2013 national security speech, President Barack Obama contrasted drone strikes with the use of “conventional air power or missiles,” which he described as “far less precise.” He also justified drone strikes, arguing that “to do nothing in the face of terrorist networks would invite far more civilian casualties.”

Scandal strategies in play

Americans watched the Jan. 6 insurrection on TV and social media as it happened. Given the vividness of the day, outright denials of the insurrection are particularly far-fetched and marginal – though they do exist. For example, some Trump supporters have claimed that left-wing “antifa” groups breached the Capitol – a claim many rioters themselves have rejected.

Some of Trump’s supporters in Congress and the media have repeated the claim that the insurrection was staged to discredit Trump. But given Trump’s own vocal support for the insurrectionists, supporters usually deploy more nuanced denials to downplay the day’s events.

So what happens when outright denial fails? From ordinary citizens to political elites, people often respond to allegations by “condemning the condemners,” accusing their accusers of exaggerating – or of doing worse things themselves, a strategy called “advantageous comparisons.”

Together, these two strategies paint those making accusations as untrustworthy or hypocritical. As I show in my new book on denial , these are standard denials of those managing scandals.

“Condemning the condemners” and “advantageous comparisons” have been central to efforts to minimize the Jan. 6 insurrection, as well. Some critics of the committee downplay the insurrection by likening it to the Black Lives Matter protests, despite the fact that the vast majority were peaceful.

“For months, our cities burned, police stations burned, our businesses were shattered. And they said nothing. Or they cheer-led for it. And they fund-raised for it. And they allowed it to happen in the greatest country in the world,” Republican Rep. Matt Gaetz said during Trump’s second impeachment. “Now, some have cited the metaphor that the president lit the flames. Well, they lit actual flames, actual fires!”

On Sept. 28, 2022, the U.S. House select committee investigating the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection will hold another public hearing – likely the last before it releases its official report.

Through earlier hearings this past summer, the committee has shown how former President Donald Trump and close associates spread the “big lie” of a stolen election. The hearings have also shown how Trump stoked the rage of protesters who marched to the U.S. Capitol and then refused to act when they breached the building.

The hearings have aired in prime time and dominated news cycles. Still, polling conducted in August by Monmouth University found that around 3 in 10 Americans still believe that Trump “did nothing wrong regarding January 6.”

As a sociologist who studies denial, I analyze how people ignore clear truths and use rhetoric to convince others to deny them, too. Politicians and their media allies have long used this rhetoric to manage scandals. Trump and his supporters’ responses to the Jan. 6 investigation are no exception.

Stages of denial

Commonly, people think of denial as a state of being: Someone is “in denial” when they reject obvious truths. However, denial also consists of linguistic strategies that people use to downplay their misconduct and avoid responsibility for it.

These strategies are remarkably adaptable. They’ve been used by both political parties to manage wildly different scandals. Even so, the strategies tend to be used in fairly predictable ways. Because of this, we can often see scandals unfold through clear stages of denial.

In my previous research on denial and U.S. torture, I analyzed how the George W. Bush administration and supporters in Congress adjusted the forms of denial they used as new allegations and evidence of abuses in the global “war on terror” became public.

For instance, after photographs of torture at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq were released in the spring of 2004, Abu Ghraib was described as a deplorable but isolated incident. At the time, there wasn’t serious public evidence of detainee abuse at other U.S. facilities.

Later revelations about the use of torture at Guantánamo Bay and secret CIA black sites changed things. The Bush administration could no longer claim that torture was an isolated incident. Officials also faced allegations that they had directly and knowingly authorized torture.

Facing these allegations, Bush and his supporters began justifying and downplaying torture. To many Americans, torture, once deplorable, was rebranded as an acceptable national security tool: “enhanced interrogation.”

As the debate about torture shows, political responses to scandal often begin with outright denials. But rarely do they end there. When politicians face credible evidence of political misconduct, they often try other forms of denial. Instead of saying allegations are untrue, they may downplay the seriousness of allegations, justify their behavior or try to distract from it.

It’s not just Republican administrations that use denial in this way. When the Obama administration could no longer outright deny civilian casualties caused by drone strikes, it downplayed them. In a 2013 national security speech, President Barack Obama contrasted drone strikes with the use of “conventional air power or missiles,” which he described as “far less precise.” He also justified drone strikes, arguing that “to do nothing in the face of terrorist networks would invite far more civilian casualties.”

Scandal strategies in play

Americans watched the Jan. 6 insurrection on TV and social media as it happened. Given the vividness of the day, outright denials of the insurrection are particularly far-fetched and marginal – though they do exist. For example, some Trump supporters have claimed that left-wing “antifa” groups breached the Capitol – a claim many rioters themselves have rejected.

Some of Trump’s supporters in Congress and the media have repeated the claim that the insurrection was staged to discredit Trump. But given Trump’s own vocal support for the insurrectionists, supporters usually deploy more nuanced denials to downplay the day’s events.

So what happens when outright denial fails? From ordinary citizens to political elites, people often respond to allegations by “condemning the condemners,” accusing their accusers of exaggerating – or of doing worse things themselves, a strategy called “advantageous comparisons.”

Together, these two strategies paint those making accusations as untrustworthy or hypocritical. As I show in my new book on denial , these are standard denials of those managing scandals.

“Condemning the condemners” and “advantageous comparisons” have been central to efforts to minimize the Jan. 6 insurrection, as well. Some critics of the committee downplay the insurrection by likening it to the Black Lives Matter protests, despite the fact that the vast majority were peaceful.

“For months, our cities burned, police stations burned, our businesses were shattered. And they said nothing. Or they cheer-led for it. And they fund-raised for it. And they allowed it to happen in the greatest country in the world,” Republican Rep. Matt Gaetz said during Trump’s second impeachment. “Now, some have cited the metaphor that the president lit the flames. Well, they lit actual flames, actual fires!”

Similar comparisons reappeared amid the House select committee’s hearings. One NFL coach called Jan. 6 a “dust-up” by comparison to the Black Lives Matter protests.

These forms of denial do several things at once. They direct attention away from the original focus of the scandal. They minimize Trump’s role in inciting the violence of Jan. 6 by making the claim that Democrats incite even more destructive forms of violence. And they discredit the investigation by suggesting that those leading it are hypocrites, more interested in scoring political points than in curtailing political violence

Trickle-down denial

These denials may not sway a majority of Americans. Still, they’re consequential. Denial trickles down by providing ordinary citizens with scripts for talking about political scandals. Denials also reaffirm beliefs, allowing people to filter out information that contradicts what they hold to be true. Indeed, ordinary Americans have adapted “advantageous comparisons” to justify the insurrection.

This has happened before. For example, in a study of politically active Americans, sociologists Barbara Sutton and Kari Marie Norgaard found that some Americans adopted pro-torture politicians’ rhetoric – such as supporting “enhanced interrogation” and defending practices like waterboarding as a way to gather intelligence, even as they condemned “torture.”

For this reason, it’s important to recognize when politicians and the media draw from the denial’s playbook. By doing so, observers can better distinguish between genuine political disagreements and the predictable denials, which protect the most powerful by excusing their misconduct.

On Sept. 28, 2022, the U.S. House select committee investigating the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection will hold another public hearing – likely the last before it releases its official report.

Through earlier hearings this past summer, the committee has shown how former President Donald Trump and close associates spread the “big lie” of a stolen election. The hearings have also shown how Trump stoked the rage of protesters who marched to the U.S. Capitol and then refused to act when they breached the building.

The hearings have aired in prime time and dominated news cycles. Still, polling conducted in August by Monmouth University found that around 3 in 10 Americans still believe that Trump “did nothing wrong regarding January 6.”

As a sociologist who studies denial, I analyze how people ignore clear truths and use rhetoric to convince others to deny them, too. Politicians and their media allies have long used this rhetoric to manage scandals. Trump and his supporters’ responses to the Jan. 6 investigation are no exception.

Stages of denial

Commonly, people think of denial as a state of being: Someone is “in denial” when they reject obvious truths. However, denial also consists of linguistic strategies that people use to downplay their misconduct and avoid responsibility for it.

These strategies are remarkably adaptable. They’ve been used by both political parties to manage wildly different scandals. Even so, the strategies tend to be used in fairly predictable ways. Because of this, we can often see scandals unfold through clear stages of denial.

In my previous research on denial and U.S. torture, I analyzed how the George W. Bush administration and supporters in Congress adjusted the forms of denial they used as new allegations and evidence of abuses in the global “war on terror” became public.

For instance, after photographs of torture at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq were released in the spring of 2004, Abu Ghraib was described as a deplorable but isolated incident. At the time, there wasn’t serious public evidence of detainee abuse at other U.S. facilities.

Later revelations about the use of torture at Guantánamo Bay and secret CIA black sites changed things. The Bush administration could no longer claim that torture was an isolated incident. Officials also faced allegations that they had directly and knowingly authorized torture.

Facing these allegations, Bush and his supporters began justifying and downplaying torture. To many Americans, torture, once deplorable, was rebranded as an acceptable national security tool: “enhanced interrogation.”

As the debate about torture shows, political responses to scandal often begin with outright denials. But rarely do they end there. When politicians face credible evidence of political misconduct, they often try other forms of denial. Instead of saying allegations are untrue, they may downplay the seriousness of allegations, justify their behavior or try to distract from it.

It’s not just Republican administrations that use denial in this way. When the Obama administration could no longer outright deny civilian casualties caused by drone strikes, it downplayed them. In a 2013 national security speech, President Barack Obama contrasted drone strikes with the use of “conventional air power or missiles,” which he described as “far less precise.” He also justified drone strikes, arguing that “to do nothing in the face of terrorist networks would invite far more civilian casualties.”

Scandal strategies in play

Americans watched the Jan. 6 insurrection on TV and social media as it happened. Given the vividness of the day, outright denials of the insurrection are particularly far-fetched and marginal – though they do exist. For example, some Trump supporters have claimed that left-wing “antifa” groups breached the Capitol – a claim many rioters themselves have rejected.

Some of Trump’s supporters in Congress and the media have repeated the claim that the insurrection was staged to discredit Trump. But given Trump’s own vocal support for the insurrectionists, supporters usually deploy more nuanced denials to downplay the day’s events.

So what happens when outright denial fails? From ordinary citizens to political elites, people often respond to allegations by “condemning the condemners,” accusing their accusers of exaggerating – or of doing worse things themselves, a strategy called “advantageous comparisons.”

Together, these two strategies paint those making accusations as untrustworthy or hypocritical. As I show in my new book on denial , these are standard denials of those managing scandals.

“Condemning the condemners” and “advantageous comparisons” have been central to efforts to minimize the Jan. 6 insurrection, as well. Some critics of the committee downplay the insurrection by likening it to the Black Lives Matter protests, despite the fact that the vast majority were peaceful.

“For months, our cities burned, police stations burned, our businesses were shattered. And they said nothing. Or they cheer-led for it. And they fund-raised for it. And they allowed it to happen in the greatest country in the world,” Republican Rep. Matt Gaetz said during Trump’s second impeachment. “Now, some have cited the metaphor that the president lit the flames. Well, they lit actual flames, actual fires!”

Similar comparisons reappeared amid the House select committee’s hearings. One NFL coach called Jan. 6 a “dust-up” by comparison to the Black Lives Matter protests.

These forms of denial do several things at once. They direct attention away from the original focus of the scandal. They minimize Trump’s role in inciting the violence of Jan. 6 by making the claim that Democrats incite even more destructive forms of violence. And they discredit the investigation by suggesting that those leading it are hypocrites, more interested in scoring political points than in curtailing political violence.

Trickle-down denial

These denials may not sway a majority of Americans. Still, they’re consequential. Denial trickles down by providing ordinary citizens with scripts for talking about political scandals. Denials also reaffirm beliefs, allowing people to filter out information that contradicts what they hold to be true. Indeed, ordinary Americans have adapted “advantageous comparisons” to justify the insurrection.

This has happened before. For example, in a study of politically active Americans, sociologists Barbara Sutton and Kari Marie Norgaard found that some Americans adopted pro-torture politicians’ rhetoric – such as supporting “enhanced interrogation” and defending practices like waterboarding as a way to gather intelligence, even as they condemned “torture.”

For this reason, it’s important to recognize when politicians and the media draw from the denial’s playbook. By doing so, observers can better distinguish between genuine political disagreements and the predictable denials, which protect the most powerful by excusing their misconduct.